by William Waites

24 Mar 2013

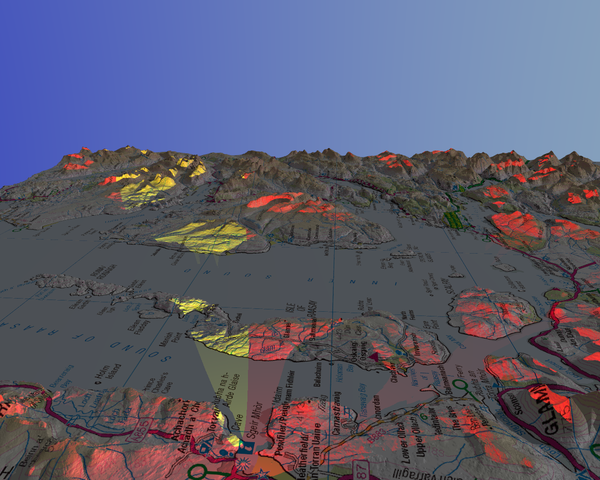

Pretty pictures with Povray

This post is about how to make pictures like this. It’s a little technical and assumes some knowledge about working with UNIX command line tools and working with geographical data. If you’re not interested in those sorts of things, then feel free to just enjoy the pretty pictures!

The first thing is the observation that radio waves behave more or less like light, at least to a first approximation. So if we have a decent 3D model of the terrain and we place a light where a radio is, whatever lights up should be pretty much the same as what is visible from that spot, and it therefore should be possible to build a radio link to there.

This is not quite true as there are two important effects that are neglected by this technique. It doesn’t account for Fresnel zones where objects that are slightly out of the direct line of sight can still cause interference. It also doesn’t account fort he curvature of the earth which can matter for longer links.

So how can we do this? High-quality computer generated 3D graphics are often done using a technique called ray tracing. This works by building up a model of a scene, the shapes of objects and what kinds of surfaces they have, then placing light sources at various points, and a camera. Then the path from the camera back to each of the light sources is calculated, reflecting off of the objects, in order to find out what colour each pixel in the resulting image should be. It’s a pretty compute-intensive process, but can give astonishingly realistic results.

A good piece of software for doing this is Povray. It’s a bit weird so far as its licensing goes, but the source code is available and it does the job nicely. If you’re planning on doing this, and want to do the rendering on a computer with multiple CPU cores, it is important to get the newest beta version to take advantage of that sort of modern hardware.

The other important bit is the data. To build the scene we need elevation data for the place we’re interested in. We also need a map of some sort to drape over it to have a better idea of where we are and what we’re looking at. This data at sufficient resolution is hard to come by. We are lucky that as academics we have access to the Ordnance Survey 1:10,000 scale Digital Terrain Model as well as the MasterMap which is pretty high quality and pleasing to look at.

This data comes in a form that is not immediately useful with Povray so the first step is getting the data into the GRASS GIS software which will let us cut it down and transform it. There is also, incedentally, an explanation of how to calculate viewsheds using grass on that page. It is likely to be more accurate but not nearly as pretty.

GRASS knows about Povray’s native format for elevation data, or what it calls height maps. First, though, set up the region so that it matches the elevation data boundaries and resolution by running

g.region rast=profile_dtm

It’s also just fine to set the extent of the region smaller, which will speed up rendering by quite a lot since Povray will have to read the whole thing into memory to do its work, so it helps to cut out any extra unnecessary data at the beginning.

Now, export the data so that Povray can use it:

% r.out.pov map=profile_dtm tga=elevation.tga hftype=1 bias=10

The last two parameters take a little explaining. The hftype will normalise the heights so that by the time they get to Povray they will be in the 0..1 range with the highest point in the data being 1. The bias parameter is because there are some negative elevations in the data, the sea is mostly in the -2m to -4m range for some reason. So that shifts everything up by 10m first.

Making sure to keep the region the same, also export the base map that we’re going to drape over the elevation data. It’s fine to use a PNG file for this:

% r.out.png map=raster_250k output=basemap.png

This is using the 1:250,000 version of MasterMap because anything more granular is terribly cluttered at the effective zoom level that we’re interested in.

Ok, that’s enough. We have our data, now let’s get Povray to put it on the screen. We’re going to try to keep using the Ordnance Survey coordinates in Povray to keep things as simple as possible. Fortunately the OSGB36 datum on which grid squares are based makes for pretty close to square pixels at least within the UK – otherwise we may have had to transform the data a bit more first. So to keep the coordinates straight, let’s get some information about the region from GRASS:

% r.region -g

n=880005

s=764995

w=109995

e=205005

nsres=10

ewres=10

rows=11501

cols=9501

cells=109271001

In our case, we only need the (n,s,e,w) values. So let’s start our Povray script with a little bit of boilerplate and then some constants:

#version 3.7;

#include "colors.inc"

#local n=880005;

#local s=764995;

#local w=109995;

#local e=205005;

#local hbias=10;

#local maxheight=1068.0+hbias;

#local hscale=2000;

The hscale value is arbitrary and serves to bring up the mountains and make the relief more obvious. To find out what the maximum height is, use this command:

% r.info -r map=profile_dtm

min=-5

max=1068.8

(in retrospect, it would have been ok to use a height bias of 5).

Now we need to set up our points. What we’re going to do here is place a radio (light) up on the hill behind Portree pointing at Arnish on Raasay. And we’re going to have the camera near the radio and looking out over the Inner Sound towards Tor Mòr on the Applecross peninsula. To do this takes a small amount of arithmetic to figure out the correct heights:

#local portree=<146740, 842710, (302+hbias)*hscale/maxheight>;

#local arnish=<159801, 847786, (110+hbias)*hscale/maxheight>;

#local tormor=<171124, 842971, (110+hbias)*hscale/maxheight>;

To find out the correct height at a particular point is done as:

% r.profile --q input=profile_dtm profile=146740,842710

0.000000 301.100006

and we just round that to 302m. Then we add the height bias and scale it according to the maximum height and our scaling factor.

Next we place the camera, high up, a little behind our site at Portree. The sky and right parameters are to fix Povray’s idiosyncratic use of a left-handed coordinate system. We like our x axis to point to the right, the y axis to point to the front and the z axis to point upwards.

camera {

sky <0,0,1>

right <-1.33,0,0>

location <135000,840000,7*hscale>

look_at tormor

}

Then the light sources. First, the ambient light. The placement of this is a bit fiddly to get right. It needs to be somewhere where it adequately lights the scene and doesn’t cause too many extraneous shadows. The second vector is the colour of the light. It is a dim white light. It needs to be dim, and fade with distance so that the lights that correspond to the radio stand out clearly, but it needs to be bright enough also so that the scene isn’t too dark.

light_source {

<e,s,50*hscale>

<0.1,0.1,0.1>

fade_power 1

}

The next light sources correspond to the radio. A red omni-directional light will illuminate everything that can be seen from the site. A green spotlight with a 20 degree wide beam will point towards Arnish on Raasay. Where these two lights overlap the result will be yellow.

light_source { portree <1,0,0> }

light_source {

portree <0,1,0> spotlight

point_at arnish

tightness 0 radius 10 falloff 10

}

The next section is the main one. It provides the backdrop for the scene and all of our lights. The image_map needs to be rotated to match Povray’s notion of what an image_map should be, and we add a fairly shiny metallic finish so that we can see the colours properly.

height_field {

tga "elevation.tga"

smooth

texture {

pigment {

image_map {

png "basemap.png"

interpolate 2

once

}

rotate <90,0,0>

}

finish {

diffuse 1.0

specular 0.8

metallic

}

}

translate <-0.5,0,-0.5>

rotate <90, 0, 180>

scale <-1,1,1>

translate <0.5,0.5,0>

scale <(e-w),(n-s),hscale>

translate <w,s,0>

}

The last section is to get our elevation map, which starts off as a 1x1x1 cube, oriented properly in our right-handed coordinate system and placed so as to line up with the native map coordinates. First we move it so that the origin is in the middle. Then we rotate it around so that it is properly in the x,y plane. Then we find that it’s inverted, so we reflect it in the x axis. We put it back so that the bottom left-hand corner is at the origin and scale it up to size. Finally we move it to the right place.

If we were to render the image now, there would be an ominous black sky. To make it nicer, let’s make the sky a nice light blue:

sky_sphere {

pigment {

gradient y

color_map {

[0.2 color <0.5, 0.75, 1>/2 ]

[1 color <0, 0, 1>/2 ]

}

scale 2

translate -1

}

}

And we also dim the ambient light a little bit more:

global_settings {

ambient_light 0.5

}

Finally we can do the rendering. This may take some time. On a fast computer with 8 processors and a lot of memory the process occupies about 1.5Gb of RAM and the whole thing takes about a minute to run. Most of the time, about 40 seconds, is reading in the data files and the rendering itself takes about 20 seconds.

% povray -d +A +W1280 +H1024 +Oportree.png portree.pov

The +A parameter turns on anti-aliasing which makes the result look nice and smooth. It does increase the rendering time significantly, though, by about double. The -d parameter stops Povray from popping up a window to briefly show the result of a rendering step.

The complete Povray script to render this image is available here.

Thanks to Schuyler Erle, Rich Gibson and Jo Walsh for their excellent book Mapping Hacks for a very useful leg up getting this to work.

Happy Hacking!